Jacob Lawrence

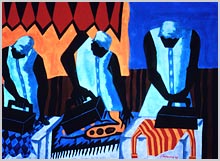

"Rent Strike"

(Because of High Rents and Unfit Conditions Rent Strikes Are Becoming More Frequent)

SOLD!

|

Go To a Lawrence biography

Go To the Washington Post review of the Lawrence traveling retrospective exhibition

Go To a list of reading and visual materials on Lawrence

Go To photographs and a sales prospectus for Rent Strike

|

The most widely acclaimed African-American artist of this century, and one of only several whose works are included in standard survey books on American art, Jacob Lawrence (17 Sept 1917 - 9 June 2000) enjoyed a successful six decade career. Lawrence's paintings portray the lives and struggles of African Americans and have found wide audiences due to their abstract, colorful style and universality of subject matter. By the time he was thirty years old, Lawrence had been labeled as the "foremost Negro artist," and since that time his career has been a series of extraordinary accomplishments. Moreover, Lawrence is one of the few widely acclaimed painters of his generation who grew up in a black community and was taught primarily by black artists.

Lawrence was born on September 17, 1917, in Atlantic City, New Jersey. He was the eldest child of Jacob and Rosa Lee Lawrence who were among the many blacks who headed north looking for opportunity. Rosa Lee had been a domestic worker from Virginia and his father, originally from South Carolina, worked as a railroad cook. In 1919 the family to Easton, Pennsylvania, where Jacob, Sr. sought work as a coal miner. Lawrence's parents separated when he was seven, and in 1924 his mother moved, first to Philadelphia and then, when Jacob was twelve years old, to Harlem. He enrolled in Public School 89 located at 135th Street and Lenox Avenue, and at the Utopia Children's Center, a settlement house that provided an after-school program in arts and crafts for Harlem children. The center was operated at that time by the painter Charles Alston who is said to have immediately recognized young Lawrence's talents.

Shortly after he began attending classes at Utopia Children's Center, Lawrence developed an interest in drawing simple geometric patterns and making diorama-type paintings from corrugated cardboard boxes. Following his graduation from P.S. 89, Lawrence enrolled in Commerce High School on West 65th Street and painted intermittently on his own. As the Depression became more acute, Lawrence's mother lost her job and the family had to go on welfare. Lawrence dropped out of high school before his junior year to find odd jobs to help support his family. He enrolled in the Civilian Conservation Corps, a New Deal jobs program, and was sent to upstate New York. There he planted trees, drained swamps, and built dams. When Lawrence returned to Harlem he became associated with the Harlem Community Art Center directed by sculptor Augusta Savage, and began painting his earliest Harlem scenes.

Lawrence enjoyed playing pool at the Harlem Y.M.C.A., where he met "Professor" Seifert, a black, self-styled lecturer and historian who had collected a large library of African and African-American literature. Seifert encouraged Lawrence to visit the Schomburg Library in Harlem to read everything he could about African and African-American culture. He also invited Lawrence to use his personal library, and to visit the Museum of Modern Art's exhibition of African art in 1935.

As the Depression continued, circumstances remained financially difficult for Lawrence and his family. Through the persistence of Augusta Savage, Lawrence was assigned to an easel project with the W.P.A. In the late 1930s, Lawrence occupied a studio at 306 West 141st Street in the company of fellow artists such as Alston, Romare Bearden, Ronald Joseph, and others. Also under the influence of Seifert, Lawrence became interested in the life of Toussaint L'Ouverture, the black revolutionary and founder of the Republic of Haiti. Lawrence felt that a single painting would not depict L'Ouverture's numerous achievements, and decided to produce a series of paintings on the general's life. Lawrence is known primarily for his series of panels on the lives of important African Americans in history and scenes of African-American life. His series of paintings include: The Life of Toussaint L'Ouverture, 1937, (forty-one panels); The Life of Frederick Douglass, 1938, (forty panels), The Life of Harriet Tubman, 1939, (thirty-one panels); The Migration of the Negro, 1940-41, (sixty panels); The Life of John Brown, 1941, (twenty-two panels); Harlem, 1942, (thirty panels); War, 1946-47, (fourteen panels); The South, 1947, (ten panels); Hospital, 1949-50, (eleven panels) and Struggle-History of the American People, 1953-55, (thirty panels completed, sixty projected).

Lawrence's best-known series is The Migration of the Negro, executed in 1940 and 1941. The panels portray the migration of over a million African Americans from the South to industrial cities in the North between 1910 and 1940. These panels, as well as others by Lawrence, are linked together by descriptive phrases, color, and design. In November 1941 the Migration series was exhibited at the prestigious Downtown Gallery in New York. This show received wide acclaim, and at the age of twenty-four Lawrence became the first African American artist to be represented by a downtown "mainstream" gallery where he met and exhibited alongside artists such as Stuart Davis, Ben Shahn, John Marin, and Charles Sheeler. During the same month Fortune magazine published a lengthy article about Lawrence, and illustrated twenty-six of the series' sixty panels. In 1943 the Downtown Gallery exhibited Lawrence's Harlem series, which was lauded by some critics as being even more successful than the Migration panels.

In 1937 Lawrence obtained a scholarship to the American Artists School in New York. At about the same time, he was also the recipient of a Rosenwald Grant for three consecutive years. In 1943 Lawrence joined the U.S. Coast Guard and was assigned to troop ships that sailed to Italy and India. He was later assigned to the first racially integrated ship in U.S. history. After his discharge in 1945, Lawrence returned to painting the history of African-American people. In the summer of 1947 Lawrence taught at the innovative Black Mountain College in North Carolina at the invitation of painter Josef Albers.

During the late 1940s Lawrence was the most celebrated African-American painter in America. Young, gifted, and personable, Lawrence presented the image of the black artist who had truly "arrived." Lawrence was, however, somewhat overwhelmed by his own success, and deeply concerned that some of his equally talented black artist friends had not achieved a similar success. As a consequence, Lawrence became deeply depressed, and in July 1949 voluntarily entered Hillside Hospital in Queens, New York, to receive treatment. He completed the Hospital series while at Hillside.

Following his discharge from the hospital in 1950, Lawrence resumed painting with renewed enthusiasm. In 1960 he was honored with a retrospective exhibition and monograph prepared by The American Federation of Arts. He also traveled to Africa twice during the 1960s and lived briefly in Nigeria. Lawrence taught for a number of years at the Art Students League in New York, and over the years served on the faculties of Brandeis University, the New School for Social Research, California State College at Hayward, the Pratt Institute (1955), Skowhegan School for Painting and Sculpture in Maine and the University of Washington, Seattle (1971), where, beginning in 1983, he remained Professor Emeritus of Art until his death.

Following his discharge from the hospital in 1950, Lawrence resumed painting with renewed enthusiasm. In 1960 he was honored with a retrospective exhibition and monograph prepared by The American Federation of Arts. He also traveled to Africa twice during the 1960s and lived briefly in Nigeria. Lawrence taught for a number of years at the Art Students League in New York, and over the years served on the faculties of Brandeis University, the New School for Social Research, California State College at Hayward, the Pratt Institute (1955), Skowhegan School for Painting and Sculpture in Maine and the University of Washington, Seattle (1971), where, beginning in 1983, he remained Professor Emeritus of Art until his death.

In 1974 the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York held a major retrospective of Lawrence's work that toured nationally. The most recent retrospective of Lawrence's paintings was organized by the Seattle Art Museum in 1986, and was accompanied by a major catalogue.

Lawrence's work is included in the major museum and corporate collections in the USA and has been exhibited internationally. Lawrence has received many prestigious awards and is a member of both the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters (since 1988) and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1995).

Lawrence met his wife Gwendolyn Knight, a fellow artist, when he was a teenager. They were married in 1941, and their close and mutually supportive relationship was an important factor in Lawrence's career.

Adapted from:

Free Within Ourselves by Regina A. Perry

Ellen Harkins Wheat, Jacob Lawrence: The Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman Series of 1938-40. Hampton, Virgina: Hampton University Museum; 1992.

Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000)

Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000)

Paper Boats (Paper Sailboats)

1949, tempera on gessoed panel

17 7/8 by 23 7/8 in.

Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery and Sculpture Garden, University of Nebraska-Lincoln,

F. M. Hall Collection

1949.H-288

Lawrence's greatest artistic and commercial success came in his genre and, as mentioned above, history paintings. His most successful series of genre paintings includes the Builders Series. Sheldon's Paper Boats, seen here, is another example of genre painting.

Lawrence was influenced by Francisco Goya and Honore Daumier, who painted very stark and politically charged artworks. He was a very skilled colorist using vivid and bold colors as did Matisse, whereby the colors would not be manipulated to look three dimensional. This flat appearance is probably Lawrence's most obvious and typical style. In his later life his experience with mental illness gave him a unique insight into the mind and he was able to convey feelings and moods with just a slouch or posture.

Richard J. Powell, in writing about Lawrence's painting (Jacob Lawrence New York, NY: Rizzoli Art Series; 1992) as a "personal philosophy of social engagement, producing a body of work that, despite its primary focus on Afro-America, informs all American culture" also says:

"Jacob Lawrence has turned stoops, staircases, ladders, and other vehicles for ascension into artistic remonstrations on survival. That all of this has been brought about by an artist who has been closely attuned to the pulse, mind, and historical edge of Afro-America should challenge us to delve even further into Jacob Lawrence's genius."

Prepared by David Barrett, Museum Studies Graduate Intern, and Edited by Karen Janovy, Curator of Education, Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery and Sculpture Garden, January, 1998.

From the Washington Post, May 27, 2001

Over the Line: The Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence

AT Phillips Collection

(1600 21st St. NW, Washington)

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Jacob Lawrence "Ironers" (Private Collection) Jacob Lawrence "Ironers" (Private Collection) |

The Phillips Collection honors one of America’s renowned modern painters. Throughout his career, the artist addressed social and racial struggles: Witness his powerful "Migration of the Negro" series. Within these powerful narratives, Lawrence was also a poet of palette and form. Color and shape appear elemental, yet transport us through some of the most complex and harrowing events in our nation’s past.

Visit the online photo gallery.

The Sure Storyteller

By Blake Gopnik

Washington Post Staff Writer

Sunday, May 27, 2001

Sometimes you start asking questions of an exhibition before you've even seen it. As soon as I finished poring over the impressive catalogue to the Jacob Lawrence retrospective that premieres today at the Phillips Collection, one query topped my list right off: Might this show prove that Lawrence, who died last June at 82, was one the greatest artists of the 20th century?

"The Migration of the Negro," Lawrence's acknowledged masterpiece, seems to argue that he was.

Painted at one go in early 1941, when Lawrence was barely 24, the panels in the series tell how throngs of black migrants made the trek from southern countryside to northern cities in the first decades of last century. Of migrant stock himself and coming of age in the rich middle of the culture of 1930s Harlem, Lawrence was perfectly qualified to be the Virgil of this uptown Rome: His images set out its founding as definitively as anyone could want.

Each of the story's 60 pictures comes with a caption that tells us what it's all about.

The text for picture No. 4 reads, "The Negro was the largest source of labor to be found after all others had been exhausted." And the image that goes with it is its perfect companion: In an empty, single-windowed room, a thin black silhouette hefts a sledgehammer, ready to pound that blue-steel spike one more time. This isn't a sanitized, New Dealish celebration of the virtues of hard work, all bulging muscles and shiny tools; it's a declaration of hard labor as the painful lot of the undernourished underdog.

Caption 15 tells about the worst tortures of black life in the South: "It was found that where there had been a lynching, the people who were reluctant to leave at first left immediately after this." Its image, rather than indulging in operatic tragedy, shares the text's laconic poise: a blank sky, a bare branch, an empty noose, barren ground, and a figure hunched in mourning. This is about the flattening effect of racist horror on the living, left behind to pull up stakes and carry on.

"Living conditions were better in the North," reads the optimistic text that comes 29 panels later, but it doesn't call for a picture of a horn of plenty. A slab of meat and loaf of bread, set against a bare-board wall, shows how little it takes to be "better" when "bad" consists of nothing.

There's a critical cliche that says that you can tell a masterpiece because it can't bear a single addition or subtraction. Mostly, this is wishful thinking. Would anybody really notice an extra crease or two in Mona Lisa's dress? But in images as spare as Lawrence's, there's some sense to the idea. We're down to storytelling at its essence here, with each image full of just the stuff it needs to do its work. No fancy oils, just store-bought poster paints brushed onto hardboard; no sophisticated palette, just a handful of well-chosen colors running clear across the series; no hard-learned tricks of perspective, just the most basic tools it takes to set one object off against another. Not only modernism's stylish "Less Is More," but a "Less Is Most" born of hard times and an urgent need to make a situation known.

The unveiling of "Migration" sent Lawrence's prospects soaring. Half the series promptly sold to the Museum of Modern Art and the other half to the Phillips, and he became the first black artist represented by a major New York dealer. Over his long life, he went on to win all kinds of honors, as well as acknowledgment throughout the art world. Even MoMA founder Alfred Barr and Bauhaus master Josef Albers, famous champions of abstraction, were early, keen supporters of Lawrence's narrative art form. But all this didn't necessarily help the fundamentals of Lawrence's reputation. He was often billed a "primitive," and paired with self-taught naifs such as Horace Pippin and Grandma Moses, or with tribal works from distant Africa. This got what he was all about profoundly wrong.

Lawrence had no formal art school education – not much would have been open to a poor black from the tenements – but his promise had been spotted and encouraged early on in the flourishing arts community of the Harlem Renaissance. Neighborhood art workshops, staffed by professionals, gave him a basic set of hand-eye skills. More importantly, his workshop mentors introduced him tothe sophisticated ways of looking at art and talking about it that was the artistic education he needed most of all. He was exposed to a modernist inventiveness that gave him license to do without the fine finish of a classical art education, and to come up with a bare-bones pictorial language that could suit his own peculiar projects. ("Migration" followed a superb 31-panel series on underground railroad heroine Harriet Tubman, which came after a 32-panel account of the life of black abolitionist Frederick Douglass, which built on Lawrence's first serial narrative, 41 images illustrating the life of Haitian revolutionary Toussaint L'Ouverture. Lawrence's first two series are missing from the Phillips show, which, at well over 200 images, still left me hungering for more.)

What's so exciting about all of Lawrence's early series is that they let us watch an artist inventing a visual idiom perfectly suited to the job at hand. This isn't raw simplicity for its own aesthetic sake, but for the sake of telling compelling stories. When Giotto fathered Renaissance realism in the 13th century, all the incidental detail that he introduced could pull you into his Bible tales, but also distract you from them; Lawrence uses the simplifications of modernism to cut right to the chase. His images are indebted to the formal innovations of European pioneers, but never mimic them just to look good.

The Phillips catalogue shows his workshop teachers slapping a superficial gloss of modernist style onto received ideas about what a picture can be of, just like most U.S. artists of their day. Their pupil, on the other hand, came up with a unique way to marry form and content. Lawrence was working out a new language of expression, not just putting on a fancy foreign accent.

This is more than just a metaphor. Words matter in the art of Jacob Lawrence more than may be commonly acknowledged. The men he came across in Harlem – figures like Ralph Ellison, Langston Hughes and Claude McKay – tended toward the verbal, and this helped shape his art. As Lawrence achieved maturity as a visual artist, the captions for his panels matured, too. The texts for "Migration," written in collaboration with his fiancee, artist Gwendolyn Knight, become clipped prose poems, close literary equivalents to the radically spare images that go with them.

Lawrence's rough technique and style – the gaps in his desultory brushwork; his coloring-book way of building up a picture from flat contours filled in one pigment at a time – bear witness to the struggle that it took to get things right. But Lawrence had to struggle not because he lacked the skills to accomplish tasks set out by others, but because he was uncovering new problems, and the skills to solve them, even as he worked.

Unfortunately, as with many artists whose success comes early, fertile struggle eventually gave way to mannered ease. In many of the excessively well crafted later pictures, Lawrence seems to have adopted a trademark Lawrencian look that rarely probes below the surface of the thing it illustrates. (He also begins to borrow more directly from other modern masters. The influence of Picasso, in particular, rather than fading away, becomes more present as Lawrence becomes a bona fide member of the high-art community.) Lawrence turns into a kind of slick imitator of the artist that he was on starting out, playing second fiddle to his younger, more inventive self. A set of illustrations for a reprised life of Tubman, painted in the 1960s, falls tragically short of the originals that hang near it at the Phillips. Only a series of pictures about Hiroshima, showing skeletons busy tending to the day to day, recaptures the urgency of Lawrence's first works.

Of course, this standard tailing off of inspiration doesn't have to reduce our estimation of the artist's early genius. But there remains another problem with giving him top billing among moderns like Matisse, Picasso or Pollock that is more complex, and which makes the question of his rank more than just scorekeeping: It may be that his art is better suited to our needs today than to the period of its making.

I'm fairly certain that, had I seen this show in the thick of the century in which Lawrence worked, my enthusiasm would not have been as great.

I hope I would have recognized and cared about the stories he had to tell, and acknowledged the genius in their telling. I am not sure, however, that I would have seen the telling of stories – any stories – as the artistic work that most needed doing. Even in the hectic 1960s you could acknowledge the importance of political activism, even participate in it, without seeing it as a likely starting point for art. There were other pressing issues in the American art world of the 20th century – abstraction to construct, and then defend against all comers; radicalisms of all kinds to make commonplace – and the powerful, direct, old-fashioned narratives you get in Lawrence might have seemed beside the point, no matter how well crafted.

Rather than imagining that Lawrence's art speaks timeless artistic truths, we may need to recognize its timefulness, and that the ideal time for it is now. The artistic battle cries of 50 years ago have faded away, leaving us free to embrace the potent pointing at the world that Lawrence pioneered. If Lawrence wasn't an odds-on, all-time great of the 20th century, he may be just the ticket for us in the 21st.

|

| |

| PRICE |

$7.50; $4 senior, student; free for member, age 18 and under |

| |

| INFORMATION |

202/432-7328 or 800/551-7328 |

| |

| WEBSITE |

http://www.phillipscollection.org/index.html |

| |

| HOURS |

May 26-Aug 19 Daily |

| |

| GALLERY INFORMATION |

202/387-2151 |

| |

| EXHIBITION VENUES & DATES |

The Phillips Collection May 26 - August 19, 2001;

The Whitney Museum of American Art New York, November 8, 2001 - February 3, 2002;

The Detroit Institute of Arts February 23 - May 19, 2002;

Los Angeles County Museum of Art June 16 - September 8, 2002;

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

October 5, 2002 - January 5, 2003.

|

| Goals and

Objectives The Jacob Lawrence Catalogue

Raisonné Project (JLCRP), established as a 501(c)(3) non-profit corporation in 1995,

is devoted to the location, documentation, authentication and publication of the

paintings, drawings, and murals of American visual artist Jacob Lawrence. The JLCRP will

present this information in a manner that affords widespread accessibility to a diverse

audience of scholars, teachers, students, and the general public.

Artwork Location and Documentation

When research began in 1995, the location of a majority of

Jacob Lawrence's work was unknown. Advances in scholarship have been hampered by a lack of

comprehensive information about the artist's work. To date, approximately seventy-five percent of the

paintings and drawings remain unpublished. Widespread access to the full scope of

Lawrence's oeuvre will provide scholars the resources for a more thorough understanding of

his contributions to twentieth-century art and culture. Since November 1995, project staff have located and documented more than 920

paintings, drawings, and murals in public and private collections throughout

the United States.

Conservation and Preservation

A greater understanding of the materials and techniques the

artist used in the early decades of his career is needed for the preservation of

these artworks.

Authentication

The increasing appearance of works falsely attributed to Lawrence coincides with the rising market value of his paintings and drawings.

The JLCRP will attempt to authenticate all located paintings and drawings with the goal of

protecting the integrity of the artist's work and career. Authentication is being conducted by a committee of scholars.

Publication Formats

Research results will be published in two formats: a

two-volume book, and an online digital archive. The book will be published by the

University of Washington Press, Seattle, and will include essays, color reproductions,

life and exhibition chronologies, and an index of artwork. The archive will contain visual and textual documentation of more than 920,

a virtual library, and an educational resource center. |

|

TWO-VOLUME PUBLICATION ON LAWRENCE'S WORK

The Jacob Lawrence Catalogue Raisonneé Project and the University of Washington Press are pleased to announce the publication of The Complete Jacob Lawrence. This two-volume book reproduces more than 900 paintings, drawings, and murals, and includes eight essays on the artist's work by distinguished art historians. The catalogue also includes a biography, exhibition chronolgy and an extensive bibliography.

The two volumes are: Over the Line: The Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence, edited with an introduction by Peter T. Nesbett and Michelle DuBois, 264 pp., 220 illus., 200 in color, index, bibliog.; and Jacob Lawrence: Paintings, Drawings, and Murals (1935-1999), A Catalogue Raisonneé, edited by Peter T. Nesbett and Michelle DuBois, 244 pp., 900 illus. 800 in color, bibliog. Price is $125 until December 31, 2000; $150 thereafter. To order, call the University of Washington Press, Seattle at 800-441-4115 (Monday-Friday, 8am-4pm PST), or order on-line at www.amazon.com.

DIGITAL ARCHIVE OF LAWRENCE ARTWORK TO BE LAUNCHED LATER THIS WINTER

A digital archive of more than 850 paintings, drawings, and murals will be launched at this address later this winter. If you want to be contacted when the archive is publicly accessible, please send us an email.

Bibliography & Resources

Other Paintings

Books

- Nesbett, Peter and Patricia Hills. Jacob Lawrence: Thirty Years of Prints

(1963-1993) / A Catalogue Raisonné. Seattle: Francine Seders Gallery and

University of Washington Press, 1994.

- Powell, Richard J. Jacob Lawrence. New York: Rizzoli, 1992.

- Wheat, Ellen Harkins. Jacob Lawrence: American Painter. Seattle: Seattle Art

Museum and University of Washington Press, 1985.

---------------. The Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman Series of

1938-1940. Hampton, Virginia: Hampton University, 1992.

Exhibition Catalogs

- Brown, Milton W. Jacob Lawrence. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1974.

- Detroit Institute of Arts. The Legend of John Brown. Detroit: Detroit

Institute of Arts Founders Society, 1978.

- Driskell, David C. Toussaint L'Ouverture Series. New York: United Homeland

Ministries, n.d.

- King-Hammond, Dr. Leslie. Jacob Lawrence: An Overview, Paintings 1935-1994.

New York: Midtown Payson Galleries, 1994.

- Lemakis, Emmanuel. Jacob Lawrence: An Exhibition of His Work. Pomona, New

Jersey: Stockton State College Art Gallery, 1983.

- Lewis, Samella. Jacob Lawrence. Santa Monica, California: The Museum of

African American Art, 1982.

---------------- and Mary Jane Hewitt. Jacob Lawrence: Drawings and Prints.

Claremont, California: Scripps College, 1988.

- Saarinen, Aline B. Jacob Lawrence. New York: American Federation of Arts,

1960.

- Turner, Elizabeth Hutton, et al. Jacob Lawrence: The Migration Series.

Washington, D.C.: The Phillips Collection, 1993.

Videos

- “Jacob Lawrence: An Intimate Portrait.” Public Media Home Vision, 1993;

published in conjunction with the exhibition “Jacob Lawrence: The Frederick

Douglass and Harriet Tubman Series” at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

- “Jacob Lawrence: The Glory of Expression.” L & S Video Enterprises Inc.,

Chappaqua, New York, 1992; produced by Linda Freeman.

- “Views and Visions in the Pacific Northwest: The Making of an Exhibition.”

Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, WA, 1990.

- “Jacob Lawrence, American Artist.” A Georgia Public Television Production,

1986.

- “The City is Ours.” Channel 9, Seattle, WA, 1980; produced by Jean

Walkinshaw.

|

Further reading on Jacob Lawrence

JACOB LAWRENCE: An Intimate Portrait

(Reference #LAW060)

This award winning video portrait offers an engaging glimpse into both the interior and exterior lives of this most influential painter, interweaving talks with the charismatic Lawrence, his wife, colleagues and critics with the painter's own magnificent works. Produced by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. 1993.

LAW060 25 min VHS

Price: $29.95

JACOB LAWRENCE: The Glory of Expression

(Reference #LSLAWR)

A documentary about the life and work of one of America's great living painters. Emphasis is placed on the epic narratives he painted about the struggles of the African-American people. Attention is given to the emotional aspects of creating art and the importance of motivation and determination for success

LSLAWR 28 min VHS

Price: $39.95

Return To Top Of Page

Browse Locally Buy Globally ®

Home |

Catalogues |

Search |

Order |

Terms of Sale |

Bibliography |

Privacy |

About Us |

Links

© 2001-2002 Coup de Foudre, LLC

|

Following his discharge from the hospital in 1950, Lawrence resumed painting with renewed enthusiasm. In 1960 he was honored with a retrospective exhibition and monograph prepared by The American Federation of Arts. He also traveled to Africa twice during the 1960s and lived briefly in Nigeria. Lawrence taught for a number of years at the Art Students League in New York, and over the years served on the faculties of Brandeis University, the New School for Social Research, California State College at Hayward, the Pratt Institute (1955), Skowhegan School for Painting and Sculpture in Maine and the University of Washington, Seattle (1971), where, beginning in 1983, he remained Professor Emeritus of Art until his death.

Following his discharge from the hospital in 1950, Lawrence resumed painting with renewed enthusiasm. In 1960 he was honored with a retrospective exhibition and monograph prepared by The American Federation of Arts. He also traveled to Africa twice during the 1960s and lived briefly in Nigeria. Lawrence taught for a number of years at the Art Students League in New York, and over the years served on the faculties of Brandeis University, the New School for Social Research, California State College at Hayward, the Pratt Institute (1955), Skowhegan School for Painting and Sculpture in Maine and the University of Washington, Seattle (1971), where, beginning in 1983, he remained Professor Emeritus of Art until his death.

Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000)

Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000) Jacob Lawrence "Ironers" (Private Collection)

Jacob Lawrence "Ironers" (Private Collection)